This treaty was engineered to concentrate the Ojibwe population in a single place, encourage them to farm through the allotment of land to individuals, and open valuable pine forests to logging. Individual band members were given scrip to be redeemed for up to 160 acres each, located within boundaries established in the treaty. Mixed blood individuals could receive scrip only if they lived within reservation boundaries, and in no case could the scrip be transferred to “any person not a member of the Chippewa tribe.” In compensation for ceding about 2,000,000 acres, the Ojibwe received $145,000, all in the form of goods and services to support education and farming, payable in various forms over a period of up to 10 years.

Over the following decades, the provisions of this treaty were abused and changed by legislation to transfer ownership of reservation lands from the control of Ojibwe people. Through legislation such as the Dawes Act and Nelson Act, lands were made available for sale to white settlers and timber interests. The Clapp rider in the early 1900's made it legal for mixed blood band members to sell their land scrip, which led to widescale fraud in which no benefits were gained for the sale.

The importance of timber interests in engineering this treaty can be found in the presence of Joel B. Bassett at the treaty signing. Serving as the U.S. Indian agent for the Ojibwe at Crow Wing (1865-1869), Basset had been a lumber manufacturer in Minneapolis since 1850, and this treaty expanded his business. By the late 1880’s, he was convicted of fraudulently harvesting 17,000,000 feet of timber from the White Earth reservation.

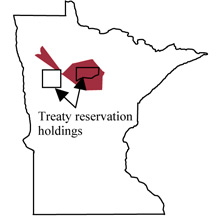

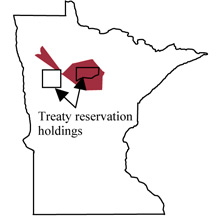

1867 Land Cessions

Henry Schoolcraft, who signed the 1825 multinational treaty at Prairie du Chien and 8 other Ojibwe treaties, first made a name for himself as a mineralogist, identifying copper and lead deposits. In 1819 he wrote a book entitled Lead Mines of Missouri that drew the attention of Lewis Cass, Michigan Territorial Governor. The next year, on an expedition with Cass, Schoolcraft bribed local Ho-Chunk men to show him the location of lead mines in the Prairie du Chien area. He was then appointed the head US Indian agent for all of the vast Michigan Territory. He appointed his brothers and brothers-in-law to positions in the Indian Affairs bureaucracy, and they signed Ojibwe treaties in what is now Michigan.

Schoolcraft's first wife was a member of a prominent eastern Ojibwe family. She shared with him the stories that became a primary source for Longfellow's Song of Hiawatha. Through a network of marriages with her relatives (French, American and Ojibwe), other treaty signers joined the same extended family as Schoolcraft. Lyman Warren became a prominent fur trader and signed treaties with the Ojibwe from what is now Minnesota in 1842 and 1837. His son Truman signed Ojibwe treaties in 1855, 1863, 1864, and 1867. Lyman's son William, who signed an 1847 Ojibwe land cession treaty, forged an identity that straddled two worlds, writing an important history of the Ojibwe people and serving in the Minnesota Legislature.

William Warren's wife, Mathilda Aitkin (daughter of fur trader William Aitkin) also had a relationship with treaty signer Samuel Abbe. Aitkin (for whom Aitkin County is named) advocated the introduction of whiskey into the Indian trade; he signed Ojibwe treaties in 1842 and 1847. Abbe wend on to the join the board of directors of railroad and canal companies, and signed an Ojibwe treaty in 1863.

Minnesota Indian Affairs Council

161 Saint Anthony Ave

Suite 919

St. Paul, MN 55103

Minnesota Humanities Center

987 Ivy Ave East

St. Paul, MN 55106