Slamming the Courthouse Door: 25 years of evidence for repealing the Prison Litigation Reform Act

Twenty-five years ago today, in 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Prison Litigation Reform Act. The “PLRA,” as it is often called, makes it much harder for incarcerated people to file and win federal civil rights lawsuits. For two-and-a-half decades, the legislation has created a double standard that limits incarcerated people’s access to the courts at all stages: it requires courts to dismiss civil rights cases from incarcerated people for minor technical reasons before even reaching the case merits, requires incarcerated people to pay filing fees that low-income people on the outside are exempt from, makes it hard to find representation by sharply capping attorney fees, creates high barriers to settlement, and weakens the ability of courts to order changes to prison and jail policies.

When the PLRA was being debated, lawmakers who supported it claimed that too many people behind bars were filing frivolous cases against the government. In fact, incarcerated people are not particularly litigious. Instead, they often face harsh, discriminatory, and unlawful conditions of confinement — and when mistreated, they have little recourse outside the courts. And when incarcerated people do bring lawsuits, those claims are extremely likely to be against the government since nearly all aspects of life in prison are under state control. 1 While prison and jail officials may occasionally feel overwhelmed by these lawsuits, cutting off access to justice ensures only that civil rights violations never reach the public eye, not that such violations never occur.

The PLRA should be repealed. It was bad policy in the 1990s — an era full of unfair, punitive, and racist criminal justice laws — and allowing it to continue today is even worse policy.

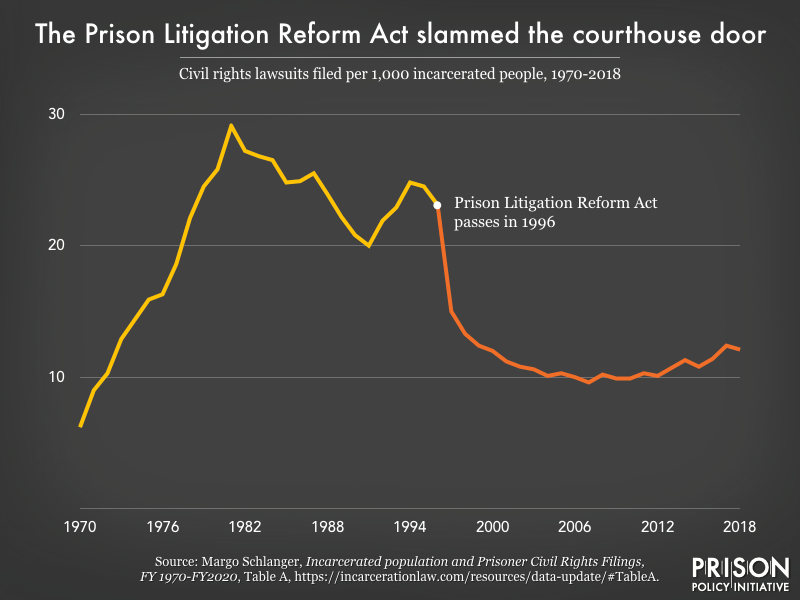

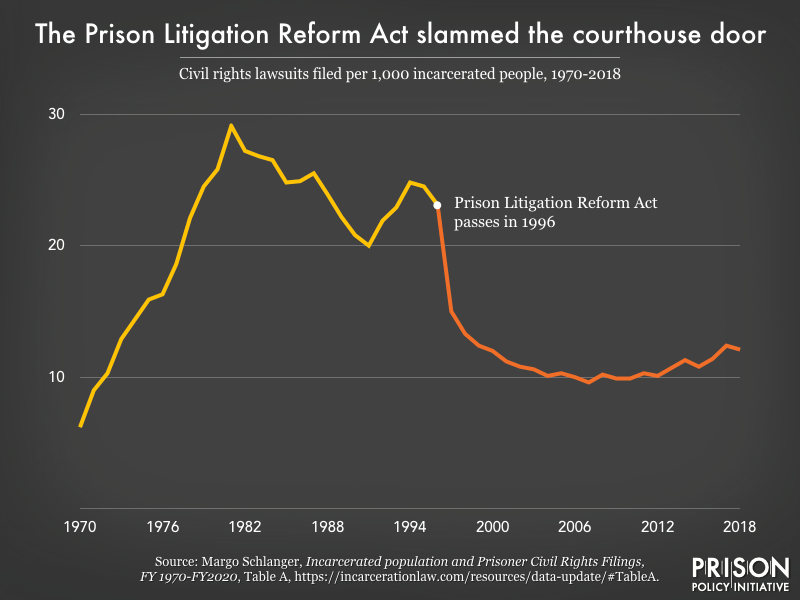

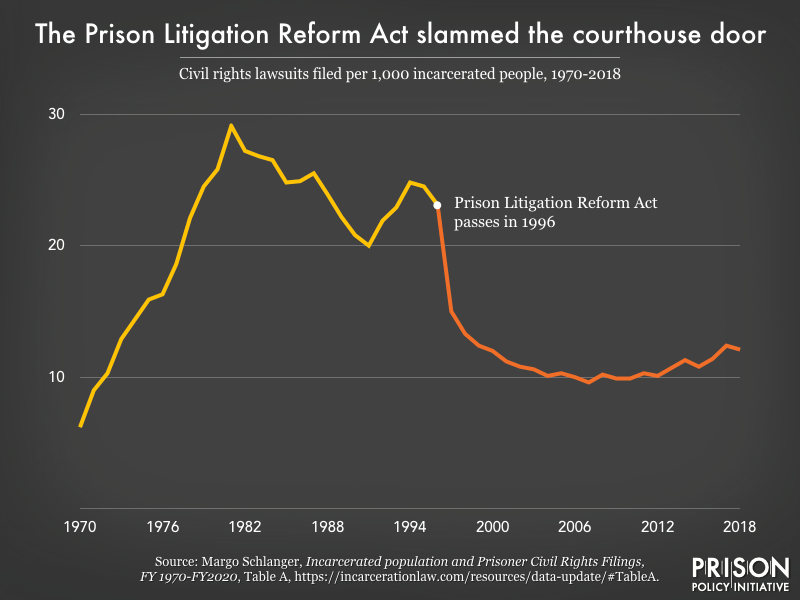

As this graph demonstrates, the rate of civil rights filings in federal court immediately dropped following the passage of the Prison Litigation Reform Act. And ironically, despite Congress’s fears of prison lawsuits flooding the courts, this data (which controls for the size of the prison population) shows that in 1996, when the PLRA was passed, the frequency of lawsuits from incarcerated people was not on the rise at all; in fact, it had already declined from its late 1970s peak. (For the underlying data, see Appendix Table A.)

The PLRA limits access to meaningful justice:

The PLRA hinders court access for incarcerated people who are trying to file civil cases — which tend to be mostly civil rights cases. It does this by making these cases harder to bring, harder to win, and harder to settle.

And when incarcerated people manage to overcome those high barriers and win a lawsuit, the PLRA limits the ability of the courts to enforce policy changes through court orders.

The PLRA makes cases harder to bring:

- Exhaustion rule: The PLRA makes many lawsuits non-starters by requiring cases to be dismissed if plaintiffs have failed to “exhaust” all of the prison or jail’s internal administrative grievance processes before taking their case to court. Working through these administrative processes can be complicated, require meeting difficult deadlines, and often prove fruitless. This allows suits to be dismissed for absurd and unfair reasons; for example, when grievances were filed in the wrong color ink or failed to meet incredibly tight deadlines as short as two or three days in some states. (See sidebar for examples of how the exhaustion rule can cause civil rights cases to be thrown out for minor mistakes in the grievance process.)

Justice denied:

Three cases thrown out due to the exhaustion rule

Three cases thrown out due to the exhaustion rule

- John Richardson sued a prison medical doctor whose egregious mistreatment of his diabetes (the doctor took him off insulin despite the fact that his blood-sugar levels were out of control) led to gangrene and the amputation of his leg. Richardson’s grievance had outlined how, as his symptoms worsened after his insulin was taken away, his multiple requests for medical care went unanswered. But when he brought a lawsuit against the doctor, that grievance was deemed insufficient by the court because he had complained about the lack of care following the doctor’s medical mistreatment, not the mistreatment itself.

- Gerald Brockington sued after being physically attacked by prison staff. The court dismissed his case for non-exhaustion; his grievance was dismissed because he had listed three issues together, instead of filing separate grievances for each of his complaints (chemical weapons while restrained, assault with a riot stick and chemical agent, and denial of medical attention).

- Derrick Mack’s case was dismissed because his grievance was denied after he submitted an internal grievance appeal using handwritten copies of prior appeals (rather than the required photocopies), without informing prison authorities that the photocopier was broken.

- Three strikes rule: Indigent people on the outside can have federal filing fees waived by bringing lawsuits in forma pauperis. But the PLRA makes incarcerated people, who make $0.14 to $0.63 per hour on average, ineligible for this waiver, meaning they must pay the $350 federal filing fee. While most incarcerated people may pay these fees by installment over time, the PLRA’s Three Strikes Rule states that after filing three claims that a judge decides are frivolous, malicious, or do not state a proper claim, 2 incarcerated plaintiffs can be required to pay fees upfront with few exceptions. This places lawsuits out of reach for nearly all the affected individuals.

And harder to win:

- Physical injury requirement: Incarcerated people are allowed to sue over unlawfully inflicted physical injury, but the PLRA restricts the remedies available in cases where people are alleging only mental or emotional harm. Many courts have interpreted this to mean that people cannot receive money damages for their prison/jail injuries unless they can show that they suffered extremely serious physical injury. 3 Many courts have also found that this provision applies even to Constitutional claims about, for example, free speech, 4 religious freedom, 5 discrimination, 6 and due process, 7 thereby denying incarcerated people the ability to seek financial compensation for the violation of their Constitutional rights.

- Discouraging experienced attorneys from taking cases: To make it economically feasible for lawyers to represent civil rights plaintiffs, Congress has entitled civil rights plaintiffs who win their cases to recover reasonable hourly attorneys’ fees from defendants. However, the PLRA imposes two sharp additional limits for incarcerated plaintiffs: it caps recoverable attorneys’ fees at a below-market rate, and insists that these fees total no more than 150% of any damages awarded to the plaintiff. But damages for incarcerated people are generally quite low, both because they don’t experience lost wages, and because (under the PLRA’s physical injury provision, described above) they often cannot recover more than nominal damages absent significant physical injury.

And harder to settle:

- Undermining settlements: In most types of litigation, parties have a lot of latitude to craft settlement agreements that fit their needs. However, the PLRA sharply limits court enforcement of settlements that include “prospective relief” — that is, a change to policy or practice going forward; enforcement is allowed only if the court has specifically found that these changes are necessary to cure the violation of a federal right. Some courts have interpreted this requirement to mean that defendants cannot merely agree that a settlement is appropriate; instead, these courts have held that either the court must have enough facts to determine that there was a violation of a federal right, or the parties must clearly stipulate that there was one. But one of the main reasons defendants in all types of cases settle is to avoid those kinds of damaging admissions. By making it so hard for incarcerated plaintiffs to settle, the PLRA takes away their best chance at a positive outcome.

For individual incarcerated people, these various barriers add up to a system where it is next to impossible to get any relief from the courts.

The PLRA also makes court orders less effective:

In other types of civil cases, judges can issue court orders, which can direct people or parties to take or not take certain actions. Historically, court orders were a major source of regulation and oversight for prisons and jails. However, the PLRA limits the ability of the courts to make these types of adjustments to prison or jail policy by shortening the lifespan of court orders and making it easier for them to be terminated. Under the PLRA, defendants can ask the court to review and possibly terminate orders about prison conditions after just two years, even if the prison or jail has not fully met all (or any) of the terms of the order. In addition, the legislation makes it harder for a court to set a population cap (which might require a jurisdiction to decarcerate) as a remedy for civil rights violations.

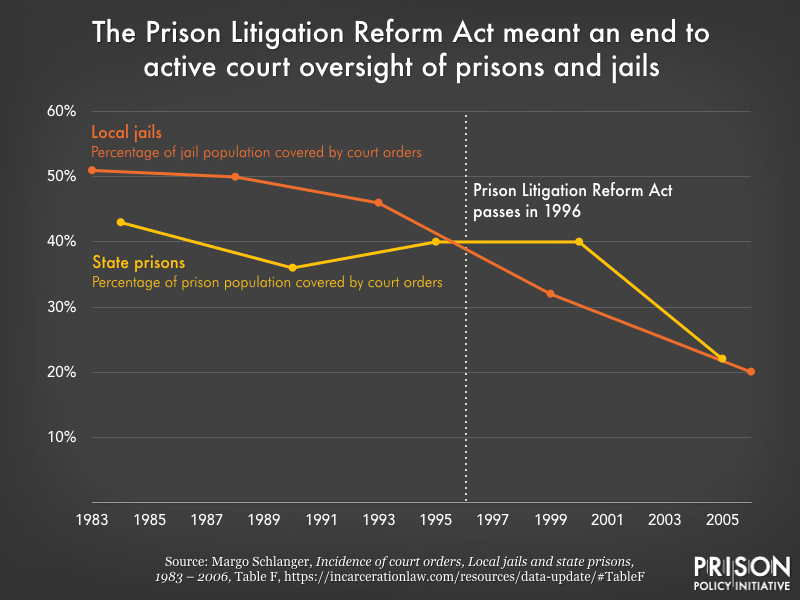

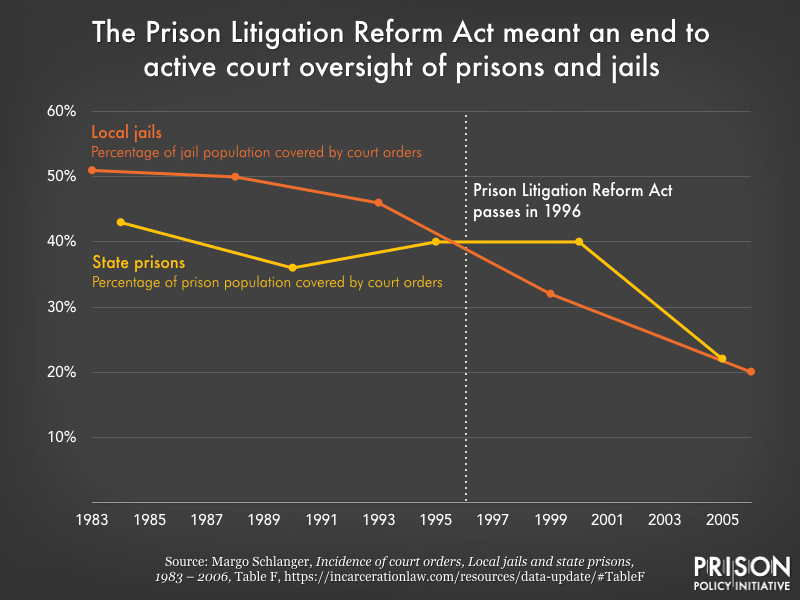

The PLRA made it harder for plaintiffs to win court oversight over prisons and jails, and easier for officials to end existing orders. In the years after its passage, as preexisting orders were terminated, the portion of the incarcerated population that was covered by court-ordered protection dropped sharply. By the end of 2006, only seven states had system-wide court order coverage in their jails or prisons. (This graph only runs through 2005 for prisons and 2006 for jails because the necessary data was not collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in its 2012 and 2013 surveys, and data collected by the BJS in 2019 has not yet been released.)

Recommendation:

It is time for Congress to repeal the Prison Litigation Reform Act. Incarcerated people do not lose all of their rights at the prison or jail door. Yet all too often, their basic freedoms are violated inside these massive and expensive public institutions, which operate largely outside of public view and with little oversight. Correctional facilities are obligated to fulfill their duties to the people under their control, and it is in the public’s interest to ensure that happens.

Yet the PLRA unjustly targets incarcerated people with disadvantageous procedural limits, making it almost impossible for incarcerated people to have their day in court, earn monetary damages for their suffering, and get and enforce prospective relief to prevent violations in the future. Repealing the PLRA is a necessary step towards ensuring that people behind bars have real and meaningful access to justice.

Methodology:

All data was collected by Professor Margo Schlanger. Prison and jail population data were obtained from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In order to obtain the most comprehensive and continuous data, prison population reflects single day counts, usually on December 31. Jail population is average daily population.

Data on court filings, case characteristics, and case outcomes is from the Federal Judicial Center’s Integrated Database. Schlanger excluded about 8,000 cases filed by one man, Dale Maisano, because their inclusion would distort trend analysis. (These cases are routinely dismissed without further processing under special “abusive litigation” court orders, so they do not impose any burden on defendants.)

Court order coverage is based on data reported by jail and prison officials in the prison and jail censuses conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics every five or six years. Since 1983, except in 2012 and 2013, the censuses have included questions about the existence of court orders on a variety of topics. The resulting data are the most comprehensive information available, despite the fact that there are important omissions. Details on omissions are available here.

Appendix of Tables:

- TABLE A:Incarcerated Population and Prison/Jail Civil Rights Filings, FY 1970 - 2020 This table depicts the underlying data for the first graph in this article. It shows the decline in the number of suits filed by incarcerated people following the passage of the PLRA.

- TABLE B:Pro se litigation in U.S. District Courts, by Case Type and Fiscal Year of Termination This table shows the high percentage of cases brought by incarcerated people that are filed pro se compared to other types of litigation.

- TABLE C:Outcomes in prisoner civil rights cases in Federal District Court, by Fiscal Year of Termination, FY 1988 - 2020 This table shows the outcomes of cases brought by incarcerated people over the past 32 years. As the table illustrates, the courts have become less and less hospitable to claims brought by incarcerated people over time. Since the passage of the PLRA, settlements, voluntary dismissals (which are often settlements as well), and trials have all declined.

- TABLE D:Outcomes in Federal District Court Cases by Case Type, Cases Terminated FY 2020 This table compares outcomes of cases classified as prisoner civil rights/prison conditions to other cases. As the table illustrates, the former are much more likely to have a pretrial decisions for the defendants, and are much less likely to settle or end in a voluntary dismissal. In the rare instances when these cases go to trial, incarcerated plaintiffs are also less likely to win.

- TABLE E:Prisoner Civil Rights Litigated Victories, FY 2012 Even when incarcerated people do manage to litigate all the way to victory, they tend to be awarded only small damages.

- TABLE F:Incidence of Court Orders, Local Jails and State Prisons, 1983 - 2006 This table contains the Bureau of Justice Statistics data underlying the second graph in this article. The portion of the incarcerated population that was covered by court-ordered protection dropped sharply a few years after the Prison Litigation Reform Act.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Katie Rose Quandt for her editorial guidance, German Marquez Alcala for work compiling data, and John Boston for his tireless decades monitoring and sharing how the courts address issues under the PLRA.

About the authors

Andrea Fenster is a Staff Attorney at the Prison Policy Initiative. She has previously written about how some prison law libraries create barriers to legal access for incarcerated people, as well as about abuses of incarcerated people in solitary confinement. Andrea’s main focus is on the Prison Policy Initiative’s campaign for prison phone justice. Before joining the Prison Policy Initiative, she worked at the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia, Equal Justice Under Law, and the Prison Law Office.

Margo Schlanger is the Wade H. and Dores M. McCree Collegiate Professor of Law at the University of Michigan Law School where she runs the Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse. She is the nation’s leading academic expert on the Prison Litigation Reform Act.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization’s reports highlight little-known but pervasive effects of mass incarceration, including in its recent reports about barriers to voting from jail and about laws that bar millions of people from juries. Alongside its reports, the organization leads the nation’s fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (known as prison gerrymandering) and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone industry and the video visitation industry.

Footnotes

- As the Supreme Court has explained, “What for a private citizen would be a dispute with his landlord, with his employer, with his tailor, with his neighbor, or with his banker becomes, for the prisoner, a dispute with the State.” ↩

- Stating a claim that is not a “strike” under these rules is easier said than done, particularly for people who are filing without legal assistance and who are unlikely to have attained high levels of education. For example, Roy Randall Harper sought damages for his emotional suffering, alleging cruel and unusual punishment after he was classified as an escape risk and moved to housing where he was deprived of cleanliness, sleep, and peace of mind. However, his damages claims were deemed frivolous, not based on its facts or a decision that no constitutional rights had been violated, but because he was barred by the PLRA from recovering damages for emotional suffering. Harper is one of many incarcerated people whose claims may be tallied as “strikes” by the strict definitions of the PLRA, despite outlining significant, real-world suffering. ↩

- For example, people incarcerated in Indiana who were exposed to asbestos were denied damages absent demonstrated physical harm. ↩

- For example, prison officials allegedly retaliated against Nathaniel Brazill for complaining to a state senator about censorship of a book that recounted the abuse of people in jail. He subsequently lost his job as a Certified Law Clerk. However, despite the fact that the court found his free speech claim to be plausible, he was unable to get compensation because he could not show a physical injury. ↩

- In one case, Daniel Mayfield alleged that he was not allowed to practice his religious ceremonies or have access to religious runestones. He was not able to seek compensation, though the court found that his rights may have been violated by the prison. ↩

- In West Virginia, Benjamin Patino Lopez was allegedly excluded from rehabilitative programming because he is Hispanic, and was subsequently prescribed anti-depressants. However, he could not show a physical injury, and therefore could not receive any compensation for the violation of his rights. ↩

- For example, Aaron Isby-Israel was unable to show physical injury after spending more than 11 years in solitary confinement; while the court found the harm he suffered to be “obvious,” he was unable to recover money damages because the harm was not physical in nature. ↩

- This statistic was collected by Margo Schlanger from the Federal Judicial Center’s integrated database, as described in paragraph 2 of the methodology. ↩